Profile: Daan Roosegaarde

“In terms of the economy, in terms of energy, the whole system is crashing and a new world needs to be discovered, somehow,” says the Dutch designer, architect and artist, Daan Roosegaarde. The trick is in finding the ‘somehow’ and in today’s tangled world, trapped in-between massive technological advancement and economic despair, with the principles of society getting lost somewhere amid the fray, we should be grateful Roosegaarde is willing to take on the task.

The key to getting out of trouble has always been society, people coming together to improve circumstances, but today real social interaction is being challenged by social networking, an impersonal experience dressed up in shimmery clothes. “I don’t believe in computer screens,” says Roosegaarde, they are one of the nightmares of our age, we call it social networking but all I see are people looking at screens.”

This increasingly digitalised world spurs Roosegaarde into action, his work in part is about reuniting people with people, tearing them away from their laptops, phones and tablets. “There are separate worlds developing,” Roosegaarde says, “there is the analogue world, Europe standing still, stalled building projects and a credit crisis, and faced with this we are connecting our dreams, our emotions, to a virtual cloud via Facebook and Twitter, there is a growing separation, a missing link and I’ve always felt the urge to join these things up.”

He attempts to do this by making our environment, the spaces people use, more human. A continuing project called Dune has won Roosegaarde praise since its first incarnation was staged in a suburban pedestrian tunnel in Rotterdam in 2007. The project is a ‘nature hybrid’, lengths of fiber optic cables creating a swaying riverbank of glowing reeds, kitted out with sensors that react to the sounds of people when they walk past. Utilising just 60 watts the project revitalized a grim tunnel by bringing people and architecture together. It prompted conversation in a space usually reserved for shuffling through with your head down, people even had their wedding photographs taken with Dune in the background.

Dune is one of many interactive projects that Studio Roosegaarde has developed in public spaces, projects that have included Marbles a set of large coloured moulded shapes that interact with people via sound, light and colour in a public square in Almere and Sensor Valley, Europe’s largest interactive sensor artwork, which interacts with human motion and touch in the Dutch city of Assen.

A more recent project, Crystal, is comprised of illuminated rocks, ‘Lego from Mars’ as Roosegaarde terms them, little pieces of glowing crystal, containing a single LED, that can be picked up and used to write and build with. “There were two agendas with Crystal,” says Roosegaarde, “one was public lighting, instead of saying here’s a streetlight, a pillar with a lamp high above you, Crystal is personal, it’s like a candle in the Middle Ages, you had the light with you then, it was hand held, you walked with the light, you can do that with Crystal.”

“The second agenda concerns communication, you can write with the crystals, you can leave messages behind, you can share them, you can steal them, they only work within an certain area, they need a small rubber power mat to charge, but with the open sourced way we made the crystals, it is possible to make your own, so you can make one for your girlfriend, then you can go to the exhibition and suddenly the crystal will burst into light like a wish fountain.” Crystal will be placed around Eindhoven during the upcoming Dutch Design Week.

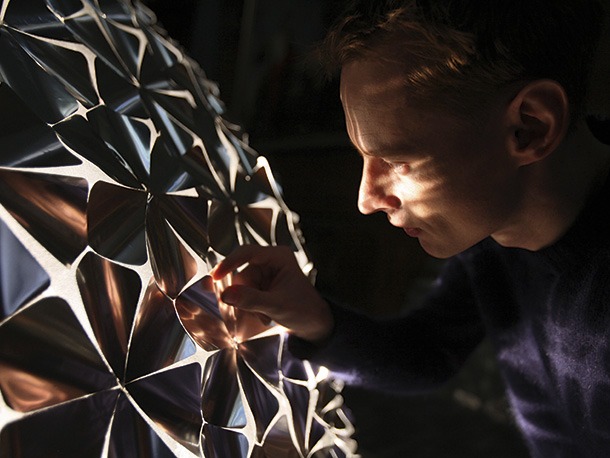

One of Roosegaarde’s most visually stunning projects is Lotus, a living dome made out of hundreds of smart flowers that fold and open in reaction to human behaviour. “Making architecture that comes alive,” Roosegaarde says, was the inspiration behind Lotus. “The project feels natural, it doesn’t copy nature but behaves like it, it feels very organic, but is completely industrialised, Lotus is very sensual,” the designer concludes, “and that is very important.”

Lotus has been placed in different locations, one of the most effective being the 17th-century Sainte Marie Madeleine Church in Lille with its beautiful Flemish Renaissance and Baroque interior, a whole host of painted Christs and Apostles coming to life when the dome is tripped into light by movement. “The church is a beautiful ornamental building,” says Roosegaarede, “but nobody went there, like a beautiful model at a party, she was lonely, because everyone was a bit scared to talk to her.”

The splendour of Catholic piety in all its seventeenth century glory doesn’t bring you closer to the Almighty, but instead overawes and leads, ironically, to a feeling of disconnection. “So we made the church dark” says Roosegaarde, “and when you walk by and the dome illuminates, you literally scan the whole building, you are rediscovering this ancient world, you are seeing what was already there in a different way.”

Lotus was also displayed in Jerusalem in Zedekiah’s Cave, a onetime quarry and the first Masonic lodge in the Holy Land. “The cave was more brutal,” says Roosegaarde, deep underneath the Holy City of Jerusalem, it was an administrative nightmare to get the piece set up, but when it was it turned visiting the cave into a very powerful, almost spiritual experience. I like updating places like that.”

Light tends to be an important part of Roosegaarde’s art. “My work is about behaviour and the type of interaction you create between people, between your body and landscape,” he says, “light is a really good medium for that. Most likely we are made of stardust anyway, so there is an intriguing relationship between light and us human beings, it is a very elementary component.”

As Roosegaarde hares off from one project to the next, he leaves behind him a set of reenergized public spaces, which fire the imaginations of the people who use them. “I’ve always wanted to make environments people can add things too,” Roosegaarde says, “that they can change, or be a part of, I think that is the kind of world that we are going to live in, one where technology becomes our second skin, our second language.”

As long as Roosegaarde continues to champion technology as something that can bring people together in the flesh, rather than through the phoney medium of a computer screen, he might be nearer to solving the mystery of that ‘somehow’ than you think.