Norwegian Official Residences, Norway

It’s easy to overlook the importance of a nation’s overseas emissaries. Though most ambassadors only come to public attention during times of intergovernmental tensions – recalled or expelled as an expression of political will – their true worth is far subtler. In addition to providing a smooth conduit for political discourse, they play a vital role in developing and promoting a national brand. The benefits of this come not only as tangible increases in global trade, but also in the development of so-called ‘soft power’ – the use of national cultural identity to improve sway in the international political and business spheres. As a venue for meeting and entertaining, the ambassador’s residence plays an important part in this process. No one knows this better than the Norwegian Government who have undertaken a program of improvements to turn their official residences into cultural outpost that immerse guests in the very best of Norway’s homegrown craft and design.

In 2009, the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs awarded a two-year tender to Norwegian interior design agency Dis, contacting them to undertake a series of projects in government spaces around the world. Such was their success in the role that the Ministry has since extended the agreement into 2012.

Dis’s work began with the Official Residence in Colombo, Sri Lanka. The team of two, Solveig Baalsrud Svoor and Ine Bangås Johansen, were given a very open brief on the project. “We had never worked with an official residence, and the client wanted to use this as an advantage and not put too many constraints on us, so we would be able to see it with new eyes,” says Baalsrud Svoor. The one proviso was that the majority of the furniture, lighting and other essential elements should in some way promote Norwegian design.

Their approach was to preserve the building’s traditional character but contrast this with feature pieces that expressed Nordic tastes. Colours were chosen that would emphasise the Scandanavian designs, but were at the same time inspired by Sri Lankan traditional clothing and their rich natural landscape. General lighting was provided locally, but Dis had the task of choosing feature lighting that could be used to create different moods within the different rooms of the residence.

Some of the lamps - such as the Big Mama from Northern Lighting, located in the living room - add an element of humour to the space. A large floor lamp, Big Mama is made out of paper and wood, considered appropriately basic and eco-friendly ‘Nordic materials’ by the Dis team. An illuminated moose head wall light - Moo, designed by Trond Svendgårdh and Ove Rogne – hangs in the dining room like a kitsch hunting trophy. As well as being a clever conversation starter, the piece works well with Camouflage, the pendant that hangs above the dining table. This piece throws out a scattered pattern of light and shadow reminiscent of the Norwegian forests that make up the moose’s natural habitat.

Snow white drops of Artemide Castor pendants hang in the hallway while the lunch/meeting room is given a splash of colourful stripes thanks to Zero’s PXL pendant. In the library-cum-office a cluster of Established & Sons Torch pendants - PVC dipped polymer cones with clear, diamond textured polycarbonate diffusers – provide top lighting whilst a Luxo L1 desk light adds a classic touch. More recently, the Dis team completed another residence, this time in Tallinn, Estonia. The design philosophy remained the same, though with a different climate and cultural location the end result was stylistically specific to host the city. Some pieces used in Sri Lanka make a reappearance: the Big Mama standard lamp stands guard in the living room this time joined by Northern Light’s Bender, a big-headed floor/reading lamp with a thin metal stand that coils up from the floor like a length of kinked rope. Modernica’s reissue of the Saucer Pendant- part of George Nelson’s 1950s bubble lamp series – hang from the room’s existing ceiling roses.

In the hallway, three glazed-porcelein Bell pendants hang with cables intertwined. The muted tones of their exterior, inspired by the rocks and plants of Scandinavia, contrast elegantly with the pure white of their inner surface. Berg wall and pendant lights in the dining room supply obvious symbolic links to Norway’s ice fields while above the dining table hangs a Hope pendant. Part of Luceplan’s collection, Hope has polycarbonate petals formed by Fresnel lenses that optimise reflection and refraction to scatter thousands of ‘icy’ shards of light across the space.

www.dis.no

The Rag & Bone Man

It takes a second to become accustomed to the scene that waits inside Paul Firbank’s Hackney workshop, a few moments to distinguish tools from materials; scrap components from works-in-progress. But then, as the brain adjusts, intriguing forms begin to pull in to focus: a wall lamp made from motorbike parts; a stool formed from a tractor seat – a host of furniture and fittings created from elements that once served a completely different purpose.

This is the home of The Rag & Bone Man, the company established by Firbank just one year ago as a brand for his unique range of reconstituted pieces. Much like the scrap he acquires on his regular trawl through the junk-yards and grease-shops of East London, the Rag & Bone Man moniker has been adopted and repurposed for a contemporary age. Whilst his 19th century predecessors merely bought and sold waste as raw materials for others to process, Firbank is very much a craftsman, embracing 21st century ideals of reuse and recycling to produce items that seem totally fresh, but at the same time have an antiqued, vintage quality.

The success of the pieces is largely down to Firbank’s ability to identify the innate beauty of quality engineering – found even in the most functional of parts. It’s a talent that suggests he has truly found his calling after a circuitous career path through an array of occupations – from tattoo artist to metal engineer and welder – eventually leading him back to his native Hackney where, in 2011, he set up the Rag & Bone Man alongside partner Lizzie Gossling.

“I started to make sculptures and lamps from found/scrap materials in my spare time,” explains Firbank. “The lamps would always generate most interest and lead to most of my sales and commissions so I decided to focus on these to see what their potential was. My first major show and launch was at Tent London 2011 where I had an overwhelming response and sold everything I had to exhibit in the first three days, giving me the confidence to go full time.”

The Rag & Bone Man returned to Tent this September after a hugely successful first year in business. On show were the workshop’s latest pieces, including a glorious chandelier, based around an old aeroplane rotary engine. Stripped down and thoroughly cleaned (using a local drive-through carwash, much to the bemusement of the garage attendants), this central body section is embellished with lamp heads created from old fire extinguisher shells. The chandelier is earmarked for the lobby of a new hotel development, the first of what Firbank hopes will become a series of commissions for large scale projects.

The engine’s second life, however, is spread further than an individual lighting fixture. As with many donor machines, different sections will eventually contribute to a variety of other works. The engine vent casing, for example, may become part of a chair, the back panel could end up as the surround for a wall clock. The continuous process of development means that the final nature of a piece will remain in flux until its completion, or until a perfect part can be found to complement a work in progress.

As word of his work spreads, Firbank’s search for materials has become ever easier, with members of the public contacting him directly to offer unusual bits of scrap. And over time, as his ability to mentally carve up existing machines in to new forms develops, the wealth of future possibilities looks ever more appealing.

Scandic Victoria Tower Hotel, Sweden

The new Victoria Tower Hotel incorporates high quality design at every level, including a collaborative first between Flos and Megaman that delivers both style and efficiency.

Standing at 118 metres tall the new Scandic Victoria Tower is a sparkling addition to the Stockholm skyline. Located in Kista, a district to the north of the city, the hotel boasts 299 rooms across 34 floors, making it the tallest not only in Sweden, but also across all of Scandinavia.

The tower has received much critical acclaim for its attention to high quality design at all scales, from the stylish exterior scheme right down to the individual visitor experience.

Architect Gert Wingårdh took inspiration from a sequin evening dress when creating the building. The triangular planes of its glass and steel façade reflect the sky and sunlight to produce a shimmering surface. Windows follow the triangular grid, resulting in an equally intriguing pattern of illumination at night. The unusual fenestration also creates refreshingly individual interiors, allowing angular blocks of daylight to enter each room in a way that constantly reminds guests of the hotel’s structural aesthetic.

Construction of Victoria Tower was driven by Norwegian investor Arthur Buchardt, who wanted the highest standard of finish for the hotel. He selected Flos fixtures for both private rooms and public spaces and, to ensure efficient, cost effective and environmentally friendly operation, these were twinned with Megaman lamp technology - a collaborative first for the two brands. Throughout the hotel’s corridors and other public spaces, 900 bespoke luminaires, including both downlighters and wall fittings, have been designed to include Megaman’s LED Par16 7W GU10 reflectors, with 35 degree beam angle delivering 600 cd beam power, and Megaman’s Liliput Plus 23W E27 CFLs.

Flos’ Easy Kap Fixed downlighters, for example, run throughout the hotel’s corridors. These fit flush to the ceiling giving a smooth, understated and natural look, aided by the LED Par16 7W GU10 lamps. Along the corridor walls, Flos’s Soft Spin fixtures sit plastered into the hotel structure to illuminate individual room numbers.

Inside the rooms, Flos’s classic Arco lamps are used to add a designer chic, while Philippe Starck-designed Ktribe floor and wall lights – fitted with Liliput Plus CFLs - add to the room’s warm ambiance.

Flos’ Mini Glo Ball luminaires, part of a range designed by Jasper Morrison, are installed around all of the hotel’s 300 bathroom mirrors. Made from white Murano glass to give off a soft white light, each is fitted with Megaman’s GU9 Series of 7W CFLs.

In the public spaces, the decorative pieces are bigger and bolder in character. Both the Lobby bar and 34th floor Skybar feature Taraxacum pendants - bubbly explosions of light designed by Achille Castiglioni. The reception area is illuminated by Rodolfo Dordoni’s Ray-S pendants and Skygarden by Marcel Wanders hang above the lobby lounge.

Whilst all the Flos fittings used ensure a high quality look, it is the lamp technology that ensures their sustainability with an estimated saving of over €300,000 and 175,000kg CO2 over the lifespan of the lighting installation.

www.flos.com

www.megamanlighting.com

Designed for Disposal

“Planned obsolescence... companies deliberately design products with a limited life, so you have to buy the same thing again.”

This is an excerpt from a video by Vitsoe, a design driven furniture company that has the ethos ‘Living better, with less, that lasts longer’.

It is in our human psychology to have the desire to own products that are new, different, more in the style of the moment and just a little bit newer. It is the ethos of the marketing and sales departments at most companies. It might even be the ethos for company objectives in general. Obsolescence plays into a human psychological ‘weakness’ and companies are very good at making use of it in order to sell more products. These are new products we don’t really need and are not genuinely better than the ‘old’ products we are replacing. Short time satisfaction that leaves us with a lot of stuff we don’t need or should have. It simply leaves us with a lot of waste. Far from being sustainable, I might add.

The problem is that planned obsolescence works so well in selling more products. It enables companies to do the single most important thing on their agenda: sell more products, and thus generate higher profits.

A clear example is IKEA. We all know them, and many of us buy products from them. Their products are relatively cheap, come in many (style) options and every year or so there is a new collection. This time just a little newer, different looking, more shiny and with a funky new colour. It is the same principle of planned obsolescence. IKEA themselves call it; ‘democratic design’ or ‘design for everyone’. “While keeping great quality,” they add.

There are a few problems with all of this. The first being dishonesty. They use the word ‘design’ to add so called value. In reality, they just add to the inflation of the word design. That does not have anything to do with good design. They call it democratic, because they sell products for a price many can afford. While that may be true to some degree, as a designer I believe this to be totally the wrong approach. Good design needs to be about better products that, as Vitsoe says, ‘last longer’. In other words, it needs to be sustainable. IKEA products are very attainable at its low retail price. To say it has high quality is just dishonest. It simply isn’t top quality. It is made of low quality materials. It is so simplistic we as ‘consumers’ can even assemble it. Most will say all of that does not matter as they want to buy new versions in one, three or maybe five years anyway. And that makes sense. At that moment it is either broken, damaged or consumers are simply tired of the look and feel of it. So we go back to IKEA and buy new stuff; planned obsolescence. All the ‘old stuff’ ends up on top of the big pile of waste. But most consumers don’t really notice that so don’t care, right?

The whole design and business approach of IKEA (and many others) is one of non-sustainability, wastefulness, fashionable and superficial aims. It has nothing to do with simplicity but everything with simplistic.

The big problem lies within the focus of most of these companies. Design for them is so often about sales opportunities, marketing objectives, competitiveness and doing something new that is in the latest style. The design of so many products is determined by profitability in the short term. Knowing people will get bored or fed up with the ‘obtrusiveness’ of the product and so throw it away and buy a new version, as explained in the IKEA example above.

A good designer’s first duty is to the user and understanding their needs, wants, use and even emotions. Design should be user-orientated. Companies should take the risk and do something that is genuinely new and better. Don’t tell everyone products are innovative just to sell them. Instead work hard and make sure they really are innovative. After all, if they truly are you don’t have to say it that much. People know they are. Good design takes time, a lot of effort, craftsmanship, focus and a mix of trial and error. Because of this, it can never report to a marketing plan, time constraint or budget. They all matter, but always as part of the design process, never the other way around.

As Dieter Rams once said, “Simplicity is the stripping away of all that is unnecessary.” What I’m saying is for all companies out there, and those most definitely include lighting companies of course, the “stripping away of all that is unnecessary” does not only have value with designing products. It should apply to companies and how they operate as well. Steve Jobs described this well for the big companies with leading market positions, in an interview he did when he said;

“When a company has a monopoly position, sales and marketing people run the company, not product people. If that company would make a better product, it doesn’t matter. The company is not going to be more successful considering them already having the monopoly position. It is the sales and marketing people who can make the company more successful. The product people get driven out of decision making forums and the companies forget what it means to make great products. The product genius or sensibility that brought the company to the monopoly position get rotted out by the people that have no conception of the difference between good or bad products.”1

Sadly, I believe the above doesn’t only happen with companies that have a monopoly position, but also others as they try to be more successful and make more money. If we really want to be innovative and come up with better products within the lighting industry (and outside for that matter) we really need to shift our goals and focus.

If companies are really as sustainable as they say they are, then they need to have fewer products that are better designed and thus longer lasting. But as of now, most companies use ‘sustainability’ as an empty marketing tool for branding. The companies that take sustainability seriously and are authentic about it are almost as scarce as the number of companies who take design really seriously.

I’m saying the things that most companies might not want to hear or take action upon, just like our parents used to do when we were children. And just like we knew as children, the people making up all those companies know we need to make the change. It is just hard to do.

Citations: 1 - Steve Jobs: The Lost Interview (2011)

Thomas Wensma is founder of Ambassador Design.

info@thomaswensma.nl

twitter.com/thomaswensma

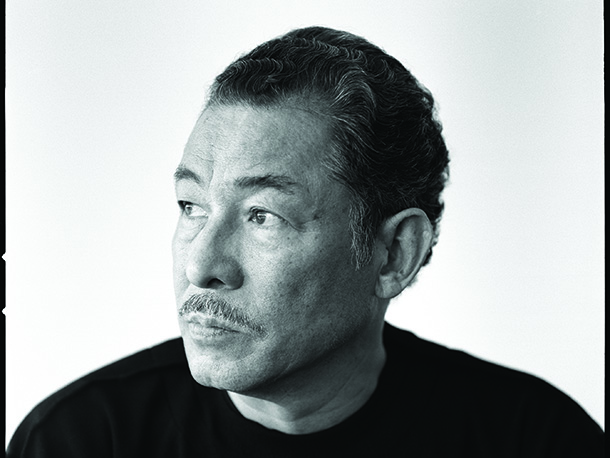

Issey Miyake

Cross collaboration between disciplines has long existed within the design community. For leading creative icons, the opportunity to apply a design philosophy to a completely new subject can prove an irresistible challenge – and one that can be rewarded with a two-way exchange of ideas and the development of wildly fresh end-products. In the Pantheon of fashion, Issay Miyake is one such icon. After founding the Miyake Design Studio in 1970 he set about creating successive collections that explored the space between the human body and the material surrounding it. Always taking a single piece of cloth as his starting point, Miyake has constantly pushed towards designing for the future, whether it be his functional and versatile “PLEATS PLEASE ISSEY MIYAKE” series (1993-) or the “A-POC” (A Piece of Cloth/ 1998-) series, that introduced a single process whereby continuous rolls of fabric, texture, and articles of clothing could be made from a single piece of thread. In many ways the worlds of fashion couture and decorative lighting share a creative border, both producing pieces that can range in style from the flamboyant to the pencil sharp. So when Miyake’s research and development team, Reality Lab, was looking for fresh applications for a new production process they had developed, decorative lighting seemed an obvious choice. The Reality Lab was formed in 2007 under the leadership of Miyake and two staff members, Manabu Kikuchi (a textile engineer) and Sachiko Yamamoto (a pattern engineer). They set themselves the goal of exploring future production methodologies, covering everything from clothing to industrial products. Their aim is to create products that reflect what people need and to find new ways to stimulate creative production in Japan. In particular there is a strong drive towards building upon the distinctive characteristics of “regenerative” materials, a response to the issues surrounding ever-dwindling natural resources. In 2010, the team unveiled “132 5. ISSEY MIYAKE”, a new way of making clothes using 3-D geometric principals encoded in a mathematical program by Jun Mitani, Associate Professor of Computer Science at the University of Tsukuba. The technology allows the creation of a single piece of fabric that can fold completely flat, but also expand out into a wearable item of clothing. It was this process that the Reality Lab felt could be applied beyond the fashion industry. Thus the team conceived the “IN-EI” series, a range of lighting pieces that were then brought to life by co-developers Artemide.

One Beam of Light curation complete

Light Collective, organisers behind the One Beam of Light project, alongside a selection panel of lighting designers and visionaries - have now performed the curation of over 380 images submitted to the international photography initiative, pairing them down to select a final 30.

Launched in October last year, the project was set up in collaboration with Concord, Havells-Sylvania's architectural lighting brand. One Beam of Light seeks to inspire and engage people interested in lighting, by focussing on a collection of photographs, all of which start with a single source of light, stripped to its bare minimum.

A traditionally unconventional medium, light artistry has spread significantly of late, and is now a very popular outlet for showcasing the creativity involved in lighting design. To help inspire participants who contributed to the One Beam of Light project, Concord donated a variety of its latest LED Beacon Projectors to aid in the creation of their images.

ISSUE TWO

INSIDE ISSUE #02:

South Place Hotel • London //

Quadrangle Architects • Toronto //

Björn Borg Headquarters • Stockholm //

Seven Shopping Centre • Düsseldorf //

Jamie’s Italian • York / Kent //

Tantris • Munich //

Folio: Igloodgn //

Comment: Nature & Nurture //

Profile: Studio Drift //

Rothschild Hotel • Tel Aviv //

Riva • Amsterdam //

Lighting Gallery //

May Design Series Preview //

Salone Del Mobile Preview //

Northern Lighting Fair //

If...

ISSUE ONE

INSIDE ISSUE #01

Google Central Saint Giles • London //

Societym • Glasgow / London //

Scandic Victoria Tower Hotel • Stockholm //

Norwegian Official Residences • Colombo & Tallinn //

Hippodrome Casino • London, UK //

Charles De Gaulle Airport • Paris //

Juicy Couture • London //

Profile: Issey Miyake //

Profile: The Rag & Bone Man //

Flos At 50 //

Comment: Design Disposability //

London Design Festival //

100% Design reviewed //

Tent reviewed //

Designjunction reviewed //